They were born after 1995. They are called "Gen Z." Before they were born, feminist struggles transformed society; one only has to think of the right to vote, the sexual revolution of the 1960s, the legalization of abortion, or pay equity. But these battles, often led by white, middle-class women, remained siloed. They rarely integrated the realities of racism, youth, religion, or gender identities, and it is precisely this vision that 11 young racialized women and non-binary people from Gen Z want to break down in the collective exhibition Briser les murs (Breaking Down Walls).

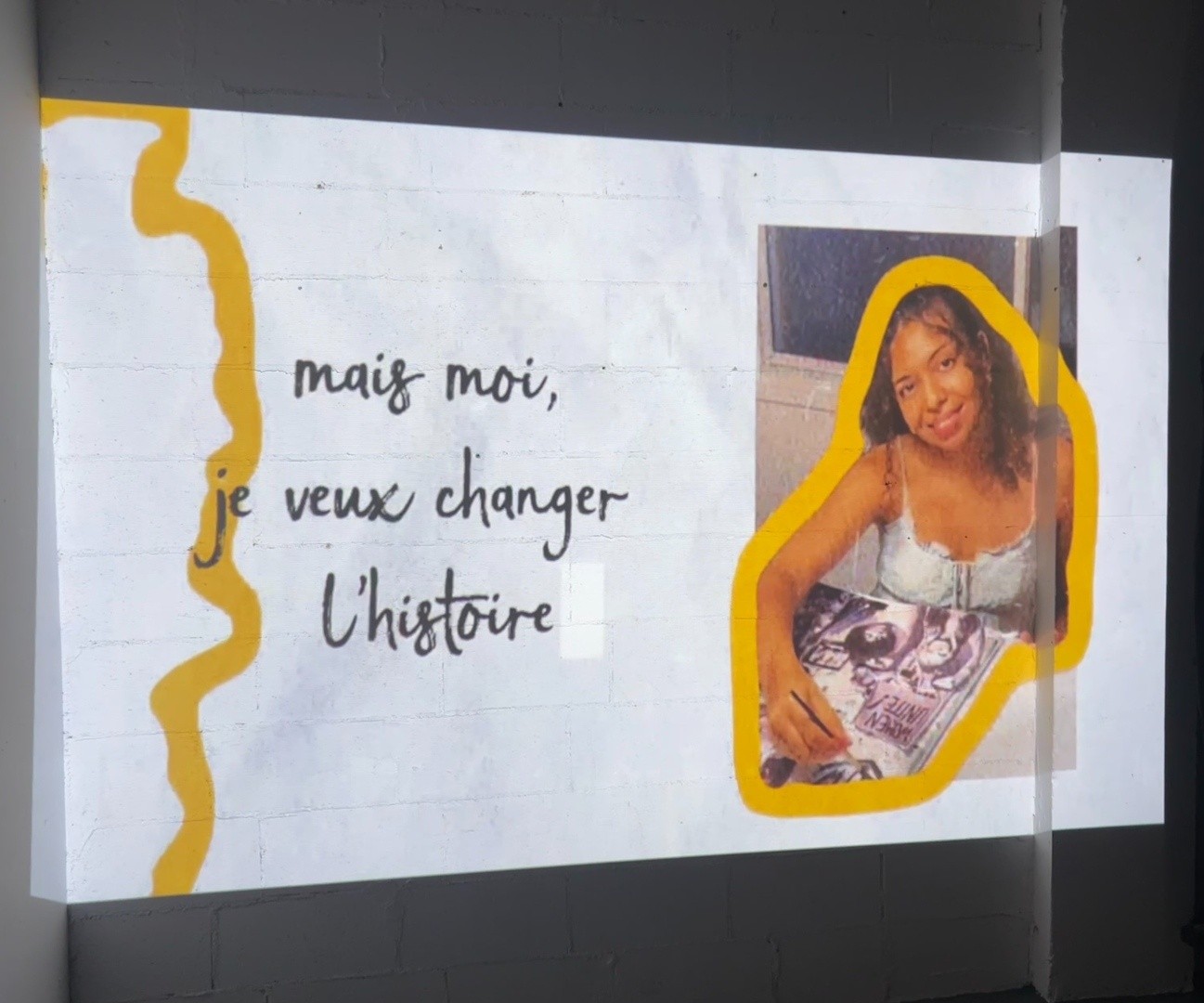

For 10 months, they worked to bring out what had previously been confined to notebooks, mobile phones, or conversations with friends. On the opening night, their photographic works, videos, installations, and performances took their place in a gallery for the first time. "We're young, we're racialized, and we don't take that for granted," says Rose, one of the exhibiting artists. "It's a blessing to have this opportunity."

For those who never imagined seeing their works hung in a gallery, it's already a breakthrough. Intimacy, anger, hope: all registers that, for the duration of an exhibition, give a voice to young people often made invisible in the Quebec cultural landscape and who, that evening, had a platform to tell their stories. We invite you to dive into the heart of this first exhibition, through the eyes of three young artists and those who came to listen to them.

It's 6 pm. Night is gently falling on Saint-Laurent Boulevard, but the street isn't sleeping. While the bars are slowly filling up and the nightclubs aren't yet open, the notes of a DJ set are coming through the window of the WIP, an art gallery. This is where the first exhibition by these young artists is being held. The event is sold out, but the doors remain open for those who are drawn in by the music or intrigued by the colourful posters pasted on the facade. "Not too young to be infantilized, not too young to be judged, not too young to face racism, not too young to lead, not too young to be sexualized," one can read. The tone is set: here, feminism dialogues with other struggles. And these words find an immediate echo with the audience. Dior, from Gen Z, sticks a Post-it on the wall at the back of the room: "Intersectionality makes us shine."

According to her, it's impossible to talk about feminism without mentioning multiple identities. "I'm a woman, but I'm also a Black woman. The issues aren't the same. A white woman can demand pay equity; I have to fight just to get hired." She points out that Gen Z goes "a little further" than previous generations in these reflections. "Our parents, for example, focused on the condition of women in general. We also highlight the blind spots, what other struggles don't take into account."

Capturing the invisible, one photograph at a time

And these "blind spots" are brought to light in a photographic, visual, and cinematographic exhibition. The artists wanted to go beyond just feminism to talk about other generational realities. "We sat down together, we put what we were living on the table, what had affected us. That's where our photos came from," says 20-year-old Rose who worked on this exhibition.

These photos express what words sometimes struggle to say: racism, ageism, and social isolation, that diffuse feeling that runs through her generation. "We tried to make people understand that you can be surrounded, you can have friends, but still feel alone. And that's what many people experience," she confides.

One of the first images the viewer discovers in the exhibition shows a woman standing still under a beam of light, surrounded by blurry figures with their backs to her. For Yann, a visitor unfamiliar with feminist debates, this photo has a profound resonance: "I still recognized myself in that photo. Because it's not a feeling only related to women. Men, too, sometimes, we can feel surrounded, but we can also feel alone." While he admits he doesn't yet have a "definite opinion on feminism," he adds, "I believe we must respect and value differences."

Another, more frontal, photo features a young Black woman in professional attire, sitting in a chair. Behind her stands a white man whose face is only half-visible, with his hands on her shoulders. "We're tired of not being taken seriously because we're young. Tired of being told we don't have the right to speak," Rose insists. It's a deliberately disturbing image that evokes racism, sexism, and this inner loneliness all at once.

Rose says this project transformed her. As a student in accounting and management, she never imagined seeing her works displayed at the WIP one day. "It's a gift, a blessing to have been able to present my photos to the public and be recognized as an artist, even if that wasn't my primary identity. It's extraordinary to have been able to experience this together, to have this recognition," she says, moved. "Being a feminist in our generation means fighting for what is rightfully ours, but also defending our culture, our choices, our freedom." Yet, feminism was not a topic in her family, she explains. "In Africa [Cameroon], it wasn't a priority. Here, my father sees what I'm going through, the difficulties, the struggles, and he understands more easily."

Finally, she highlights a tension that, according to her, strongly runs through her generation: "We try to be freer, but we get sexualized much faster." Between the desire for emancipation and a reductive social gaze, this is, in her eyes, one of the great feminist issues of our time.

When the screen reflects wounds

To 19-year-old Myriam, "feminism is a voice." A universal and unifying movement that helps make things happen. She found this voice in cinema.

In a small room at the back of the gallery, her short film plays on a loop. It's an audiovisual collage that she narrates and which addresses the theme of violence against women. "I made a short film talking about violence, whether it's street harassment, sexual assault, and everything that comes with it," explains the artist, whose work comes from a personal experience.

"The idea of people's gazes on my body makes me feel like a piece of meat," she says. "It's not because of the outfit; it's because we live in a society where we are only seen as objects for satisfaction."

Her film doesn't stop at visible assaults; it also addresses less obvious but equally destructive wounds. Gaslighting, manipulation, guilt-tripping... all forms of psychological violence that leave their mark. "We talk a lot about physical or sexual abuse, but not enough about mental violence. Yet, that's also destructive," she insists. "I wanted to find the courage to talk about that," she confides.

Originally from Morocco, Myriam remembers experiencing street harassment as a teenager, but also more recently in Montreal. "I started to see people calling out to me on the street, not with 'insults' but with words to try to hit on me in a more perverse way," she recounts. For her, this phenomenon transcends borders. "It exists everywhere. You could be a tourist in another country, and every man you walk past will call out to you," she says.

With her film, Myriam primarily wants to show that this violence should not condemn women to silence or isolation. "I wanted to show that you can always find the courage to speak and ask for help so you don't feel alone."

She finds images have a special power. More than words, cinema allows her to give form to her experiences and share them. Seeing her short film projected on a big screen in a packed room transformed this personal experience into a public statement.

In the room, silence reigns. Sophie, a viewer, says as she leaves that she was deeply moved by Myriam's film. "The images, the words, everything resonates because these are realities that many women know," she says. For her, the choice of audiovisual collage strengthens the power of the message: "You feel that it's not just a personal story, but something that concerns all of us."

Myriam points out that her approach is also a quest for solidarity. "I wanted to show that women can connect with each other, not feel alone." Before Fem-Artz, Myriam didn't define herself as a feminist, for lack of a role model. The collective gave her a space to experiment, put words to her intuitions, and understand that her personal experience could be similar to that of other women.

For her, feminism is also refusing the repeated injunctions placed on women: to get married, seek a man's validation, and dress to please. "We don't need a man to tell us who we should be," she states.

Dialogues between generations: yesterday's memories are today's hopes

The event is in full swing, the music continues to vibrate against the walls, and in a corner of the room, Asmaa stares at the photos for a long time. A member of the Canadian Council of Muslim Women, she knows all too well the importance of these collective moments. For her, this exhibition is a reminder that the next generation is indeed here. "In our feminist organizations, it's often older women. We need to encourage young people to take their place. It's the future," she declares with conviction.

Originally from Egypt, she arrived in Canada in the 1960s, at the very moment when Western feminism was redefining itself. "It was the beginning of feminism in the United States; we saw women wanting to take their place. And it was also the sexual revolution, the arrival of the pill," she recalls.

For the young adult she was then, it was a shock: leaving a country locked down by an authoritarian regime where it was not only forbidden to talk about politics but also social change, to discover a society where women could express themselves, protest, and study. "I wanted to flourish, to live in a more open society."

Today, in front of the works of Rose, Myriam, and the others, Asmaa says she sees a passing of the torch. She notes the differences between her era and that of Gen Z. "In my time, there were fewer subtleties. It was women versus men. Now, young people talk about gender equality, intermediate realities, non-binary people." She sees it not as a break, but as a continuity. Each generation, she says, reinvents its battles.

Her view remains realistic. She knows that progress can be reversed. She cites the example of the United States, where the right to abortion has been challenged in several states. "Progress is never guaranteed. That's why we have to keep fighting," she insists. Yet, despite her clear-sightedness, Asmaa says she is full of hope. Seeing these young racialized people exhibit their works for the first time, giving form to their wounds and their struggles, is a promise for her. "The essential thing is that the chain doesn't stop. Each generation has its own urgent issues, but we must never break the thread."

Not far away, Morgane, a millennial and a social worker in the field of domestic violence, looks around her attentively. To her, it's not just an exhibition but a reminder: "The same themes are coming back, but it's very significant. It means something." She mentions the body, invisibilization, sisterhood, the difficulty of learning to love oneself, of building oneself in the eyes of others. "These are the same realities, the same battles that I had to face and continue to face," she says, her voice calm.

She does not see a radical break between millennials and Gen Z members, but rather another way of speaking out: "Maybe the difference is in the way they approach it, the way they vocalize it. They show it through art, in an exhibition."

She admits that she had some apprehension before coming: "With all the statistics we hear, I was a little afraid that Gen Z was going back to more traditional values. But what I saw here are rich, unique approaches. Each person has their own way of expressing their struggle."

What struck her most was the expression of bodies: the dance performance, but also the physical presence of the artists in the room. "It was well-placed, not disjointed. It was about taking up space, being comfortable in one's body," she points out. And she concludes with a smile: "There's a new generation. It's interesting, and above all, reassuring."

Alexandra, also a millennial and a seasoned activist, says she is "reassured to see that the next generation is getting involved and that BIPOC voices, rarely heard, can be exhibited."

Coexisting, connecting, fighting together

The evening is in full swing. Spectators move from one photo to another, stop in front of an installation, and continue their walk toward a video. The flow is continuous, almost organic. In the middle of this movement, a silhouette stands out: 19-year-old Ritej also walks around, but with particular attention. She stops, exchanges a few words, and explains an image to anyone who asks. Sometimes, she simply answers a question, giving a knowing look at the work she helped stage.

With others, she thought about the scenography of the exhibition: how the arrangement, the lights, and the colours could extend the message about the nature of feminism for Gen Z. In the gallery, blue and orange lights, two seemingly opposite shades, coexist to create an unexpected harmony. A visual metaphor for what Briser les murs seeks to make people feel: differences that, put together, compose a common narrative. "That's what we wanted people to feel: even if we're different, we can mix, coexist; and it becomes beautiful."

This quest for harmony resonates with her own journey. Originally from Montréal-Nord, Ritej says how this project allowed her to open up. "I met people who are not like me, who come from elsewhere. It changed the way I see things," she confides.

She defines her feminism as a form of humanism: "Everyone deserves to live fully, without discrimination." She extends the struggle to injustices based on religion, skin colour, sexual orientation, and appearance. Ritej wears the veil and knows the prejudices that come with it. "People often say that feminism doesn't exist for veiled women. But that's completely false. My veil doesn't define me. It's a choice I make for myself, not for men. For me, it fits perfectly with feminism: choosing what you want to do with your body and your life."

She insists that even if she doesn't directly experience all the forms of discrimination, she fights for those who do. "Just like our ancestors fought for us," she says, convinced that each generation must play its part in the chain of struggles.

"When we talk about collective liberation, we all have our part to play," recalled the project and mobilization officer for Fem-Artz, Taïna Mueth, in the exhibition's opening speech. That evening, her words found a direct echo in the works and voices of the young exhibitors: breaking down the walls between struggles, refusing to compartmentalize battles, and showing that personal experience can become a collective force.

Did you enjoy this article?

Every week, we send out stories like this one—straight to your inbox.

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

%20(2).jpg)

.png)