The Black Healing Centre is a nonprofit created by and for Black communities that has been around for five years. But until recently, it had no physical space to host its activities. Since the end of April 2025, the centre finally has a home base, right in between the Côte-des-Neiges and Notre-Dame-de-Grâce neighbourhoods in Montreal. With a permanent lineup of services like collective care circles, and one-off events such as candlelit yin yoga sessions, open mic nights for Black queer and trans folks, and writing or mindfulness workshops, the space has become a vibrant community hub where Black-focused healing thrives. Let’s take a look back at what this space represents to its members, and what occured on its opening night this past April.

The birth of a sanctuary

It was a rainy evening in late April 2025. The Queen Mary Health Complex at 2100 Marlowe Ave seemed deserted. Most rooms were in pitch darkness—except one, on the 4th floor: the Black Healing Centre.

The decision to settle near Vendôme metro wasn’t random. It’s right where the community lives, with a clear purpose: to offer services that are accessible and grounded in the day-to-day realities of those they serve. Too often, community spaces are far-flung and hard to reach.

To get there, you had to first navigate the building’s quiet maze: dull-colored hallways, discreet elevators, hidden staircases. A journey that felt like a well-kept secret, until you reached suite 449, where the opening celebration was taking place.

Inside, the contrast was striking. Around fifty people were hugging, exchanging knowing glances, and full-bellied laughter. A palpable sense of collective pride permeated in the air. This place was long dreamed of—but almost didn’t come to be. Too expensive. Too Black. Too community-centered.

“We lost a lot of money. We had to face many white folks telling us: ‘No, you can’t be here,’” said board chair Danièle-Jocelyne Otou at the top of her speech. “Just six months ago, God knows we were about to pull the plug. But we didn’t—and I’m so glad we didn’t. We deserve a space to care for ourselves.”

Even though doors had kept closing, today the space is real. Clinical director and psychotherapist Dr. Lisa Ndejuru shared her joy in her speech: “The space isn't just four walls. It’s the people. It’s the dream made real.”

Ndejuru gave attendees a verbal roadmap of the collective tunnel they’d journeyed through to get to this point. The room fell silent.

“This work began before the world was on fire, before George Floyd exhaled his last breath [...] We didn’t look away. We stayed. We leaned on each other. We cried. We worked. We planted. We harvested hope from the soil. The world is still fighting. It hasn’t stopped. But we’re keeping the fire alive.”

Her words were met with quiet 'amens' in the crowd.

The search for a safe space

Behind the walls of the Black Healing Centre is also the deeply personal story of its founder, Samantha Nyinawumuntula. It constitutes a long quest for a safe space to feel seen and understood.

Her first therapist wasn’t Black, she recalls in a calm, steady voice. “I remember ending the session thinking, ‘I don’t think this is for me.”

During the pandemic, the lack of dedicated mental health spaces became even more glaring. “Everyone was on a year-long waitlist for a CLSC (local community service centre) or to find a therapist. And when you factored in Black therapists, they were overwhelmed and exhausted too.”

To respond to this issue, Samantha took action. In 2020, the idea of creating a space by and for Black people started to take shape as the effects of isolation and stress were sharply felt. She surveyed the community. The question was simple: “Would you want a centre dedicated to our well-being?” The answer was a resounding yes.

“Everyone said yes. A centre for Black wellness—that’s something we want,” Samantha recalls.

By 2021, the first services were being offered. Over time, the centre's permanent programming took form and introduced collective care, a training program for community care practitioners, and retreats. At the Black Healing centre, mental health is approached differently than in the mainstream by reconnecting body, history, and identity, in intentionally non-mixed spaces, through Afrocentric, community-based, and intersectional approaches.

Black healing, collective power

Popularized by African American scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, the concept of intersectionality explains how different forms of oppression such as racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia overlap and intensify one another.

For Niyinawumuntu, mental health conversations must include this lens: “Well-being also means thinking about intersectionality: Black people are not all the same.”

This approach takes shape through collective healing circles rooted in Afro-Caribbean traditions, tailored for women, men, queer and trans people. Each circle lasts 12 weeks and often ends with a retreat in nature. Facilitators share similar life experiences with participants, because healing paths can’t be one-size-fits-all.

For men, however, mental health often remains taboo and is a topic surrounded by greater pushback and resistance. When the program for women launched, many of them asked, “What about us?”

Creating a safe space for men required different entry points. They didn’t want to hear the word “healing” outright and instead expressed a preference for different activities and a different vocabulary. This inspired wellness days held in barbershops for instance, spaces where Black men feel naturally comfortable.

Thus their interest in mental health wellness is real, but including them in the design of these programs is essential to meet their specific needs.

Healing also means reckoning with inherited wounds passed from generation to generation. For Samantha, systemic racism and colonial legacies have left deep scars that still impact Black communities today.

“We need to build community connections and multiply these conversations. Not to water them down, but to offer more spaces where we can talk about our experiences within our communities. It will help people begin to understand what intergenerational trauma really means, because for many, it’s still a new concept.”

She adds that, “It’s not just what your parents passed on. It’s also what you lived through in school, at work, and in other systems.”

“For most of us, we’re part of the first generation to even begin this work. We’ve been carrying this weight for 400, 500 years [...] That legacy still shapes how we act and react.”

Collective healing is a long process. It takes time and patience. Samantha insists it starts with a personal commitment which begins with becoming aware of what you’re going through, identifying your needs, and seeking the right support.

Most services at the Black Healing Centre are free or low-cost, making healing accessible to more people.

“I learned how to breathe”

Manda, also known as Miss Benn on the CKUT community radio, has been going to the centre since its early days. Born in Quebec and raised in a Caribbean culture marked by silence around mental health, she shares that “[Her] parents didn’t talk about mental health. You just lived through it—period.”

That silence followed her into adulthood, and into institutions that were meant to help her out of this mental block. She recounts her experience with mainstream mental health services like CLSCs, which she found were disconnected from her reality.

“They don’t understand our history. You don’t even live in my neighbourhood. So how can you understand what we go through when we talk about abusive landlords?”

To her, traditional mental health care may be well-intentioned, but it often fails because it doesn’t account for the cultural and social contexts of those it aims to help. That gap led her to conclude that the system “just wasn’t for her.”

The Black Healing Centre offered something new. It was a space where she finally felt recognized in both her identity and her struggles. She decided to “get to the root of her trauma” and joined the Black women’s collective care circles.

“There are no words to describe them," says Manda.

She recalls those first sessions, full of silence, broken by tears. It was simply a moment of crying together, in a safe space. It was an act of liberation.

Manda recalls an exercise that shook her. Participants were asked to feel present within their body, from head to toe. Manda couldn’t do it. The facilitator gently pushed her further to release her blockage. In that moment, Manda realized she had never grieved her mother, who died ten years earlier.

“I didn’t know I had mommy issues. We talk so much about daddy issues, but we forget our mothers.”

Through this work, she understood that some of the weight she carried wasn’t hers. It was inherited pain. Pain that needed to be unpacked to move forward.

“The things we carry are heavy. We’ve got bricks in our backpack, and it’s about learning to let them go.”

At the Black Healing Centre, she says, she found a new strength and a path to mental and spiritual healing, through collective recognition and sisterhood.

“I learned how to breathe. Literally,” adds Manda.

Today, Manda is training to become a practitioner in ancestral healing with the Black Healing Centre. The training helps her deepen her skills so she can guide others through their own healing journeys, through culturally grounded, community-based practices rooted in Black realities.

She knows healing isn’t magic. Everyone moves at their own pace.

“I wouldn’t say the Black Healing Centre is going to ‘save you’, because that sets unreasonable expectations. But I can say you’ll find refuge. And sometimes, that’s all you need to start.”

The beginning of a release

At the opening celebration, every gesture, every word seemed to communicate a feeling of achievement. 'We made it. Finally.'

Sayid, a father who came with his daughter, said having a physical space like the Black Healing Centre was “crucial.” Walking through its doors, he felt a deep sense of belonging.

“When you see people like you, who are dealing with similar issues, who you can share your stories, your hopes, your wins with, it feels incredible,” explained Sayid.

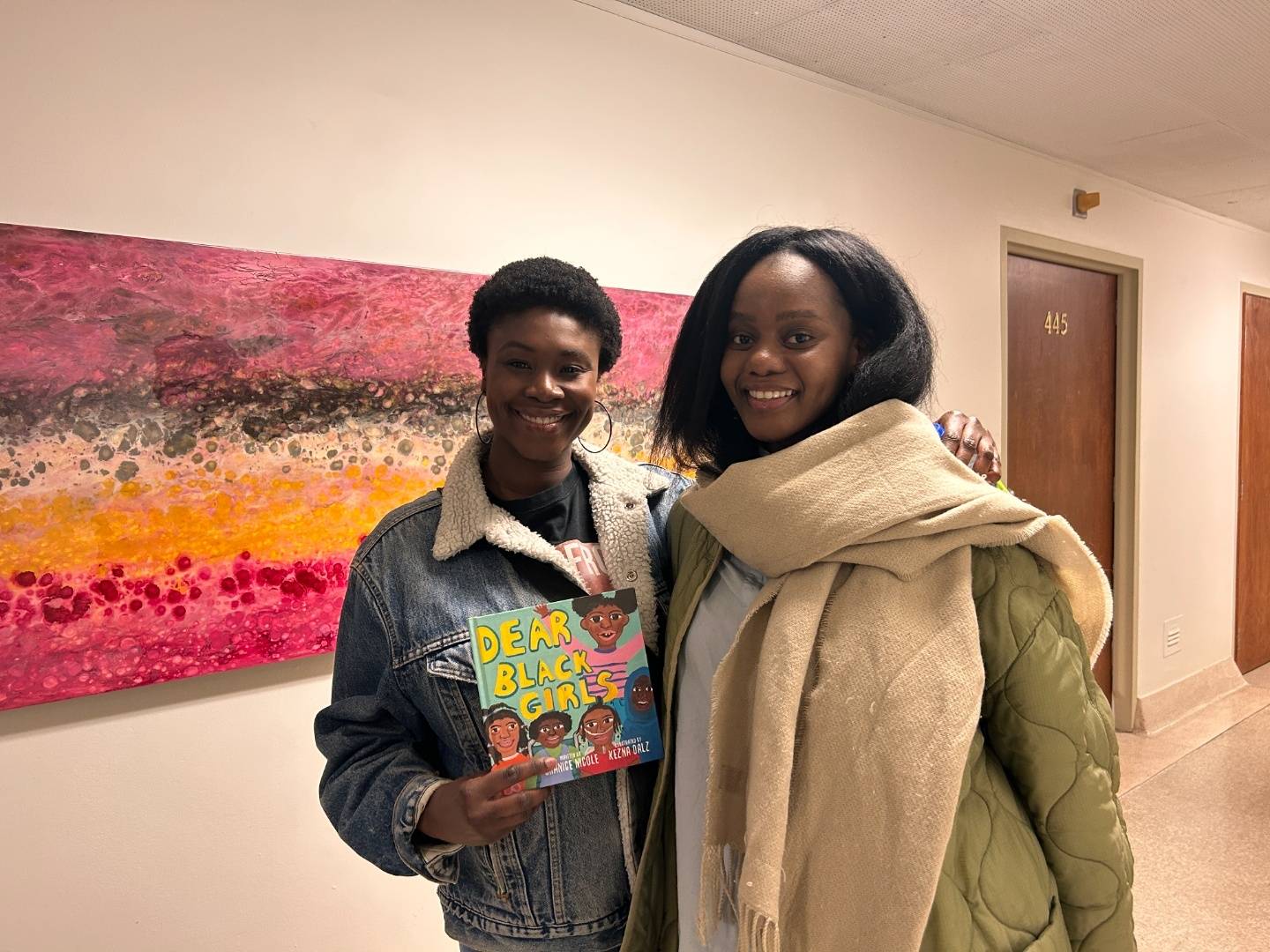

As the evening wrapped up, two other guests, Patricia and Princella, left the room with an energetic glow to them.

“I think it’s so important to have a space that reflects the Black population,” said Patricia. “There’s so much trauma passed down from all kinds of histories. And I think it’s been a long time coming, that we start unloading that trauma.”

It’s time for Black community members to go to therapy and say the quiet part out loud, she insisted: “We’re really seeing mental health becoming more normalized in the Black community, for women, men, and children. It’s important to claim that, and to normalize it.”

In the centre's common area, a collaborative painting by artist Kezna Dalz featuring flowers, faces, and the message “Intentionally Healing” serves as a living imprint of the evening. A reminder of the presence and dedication of everyone working to shift the paradigm.

Visit the Black Healing Centre's website: https://www.blackhealingcentre.com/

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)