Haphazardous decisions, the high demand in immigration programs, and backlogs pushes international students, foreign workers and refugees to apply for Humanitarian and Compassionate reasons as their last shot to stay in Canada. However, few obtain a positive decision from their claims since there are many obstacles in their way to secure a status.

Angie Sanchez arrived in Montreal in September 2022 as an international student with her husband and two kids. They decided to immigrate from Colombia, their home country, to find a place where their kids could grow up safely.

“For the sake of the children's safety. That was the main factor. Secondly, because we wanted to change our lifestyle, to have a quieter life in terms of stress, chaos, and we wanted to interact with different kinds of people,” explains Sanchez.

Before immigrating, she and her husband were considering Spain and the U.S, apart from Canada because they had family members living in those countries.

“When we were looking at options for leaving the country, we always wanted to find a way to do it the right way, legally. At that time, Canada with its student program was the option that appealed to us the most,” says Sanchez.

What was appealing for her and her family is that international students in Canada can study and work up to 24 hours a week off campus. They can also be accompanied by their children—who can continue their studies at school—, and spouses or common-law partners, who are able to work full time for any employer in Canada through an open work permit.

After deciding to come to Montreal, Sanchez applied for a study permit, a federal document that allows foreign nationals to study at designated learning institutions. Here, she planned to become a legal assistant and eventually apply for permanent residency with her family.

“We saw more opportunities for a future here,” says Sanchez.

While she was pursuing her studies, she applied for an extension of her study permit. However, due to delays of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), Angie and her family are now without status. Their last resort to be able to stay in Canada was to apply for permanent residency on humanitarian and compassionate grounds.

“There were administrative errors in my immigration file from the beginning”

Sanchez’s initial plan was to study in English, however, by that time, in 2023, the Quebec Experience Program (PEQ), an immigration option that provides a fast-track for foreign graduates and workers to settle in Quebec, stated that candidates interested in this program must have an eligible diploma of study in French.

Therefore, Sanchez decided to focus all her efforts into learning French and finished her legal secretarial studies in that language. To meet the requirements to apply for permanent residency, she needed to complete a training program —an Attestation of Vocational Specialization (AVS), to comply with the minimum of 1800 hours of study.

A year after arriving in Canada, Angie was already working as a community immigration worker at the Paralegal and Social Orientation Center for Immigrants (COPSI), a non-profit organization in Rosemont-Petit Patrie that offers services to low-income immigrants and refugees, especially from Latin America.

She found the offer in a Facebook post from COPSI, which said that they were looking for a community immigration worker who spoke French and Spanish. Since her studies as a legal secretary were related to the immigration field, she applied for the job opening.

“I ended up working in this field, or rather, I stayed in community work because my mother in Colombia has worked her whole life in social services, community work, and so on, so I've been very involved in this type of work my whole life,” says Sanchez.

Her work at COPSI includes supporting and assisting people with their immigration processes.

In July 2024, she applied for an extension of her study permit because it was going to expire before she finished her training program.

“According to the [IRCC] website, when I applied, there was a 180-day wait for a response. Those 180 days were up on December 23, 2024, and by that date, I still hadn't received a response,” continues Angie. “I called immigration, I sent web forms, and all they told me was, ‘Wait, you have to wait’. They always told me that everything was fine, that everything was correct, that it was just a matter of waiting.”

She called everyday to IRCC to check the status of her application. On one of these calls, a worker told her that her case was going to be reviewed by a supervisor due to the delay.

Seven months after filing the extension for her work permit, Sanchez received in February 2025 a letter from her college, the École des métiers de l'informatique, du commerce et de l'administration (EMICA) saying that she couldn’t continue with her studies because her study permit had already expired. She was supposed to finish by March 2025.

Sanchez also applied for an extension of her Certificat d'acceptation du Québec (CAQ) because it was going to expire and she hadn’t finished her studies. This is a mandatory provincial immigration document for international students and workers who intend to reside temporarily in Quebec. When renewing the CAQ, international students must submit an application for a new study permit.

Eight months after having applied for the extension of her study permit, Sanchez received a letter from the IRCC saying that her request was denied because her CAQ had expired.

“It was really frustrating. After eight months and eight days, just when my CAQ had expired, I received a response. Their decision was based just on that,” believes Sanchez.

She had to stop working at COPSI because she lost her status as an international student. Her husband lost his work permit as well, because it was tied to Angie’s process since she was the main applicant. Their kids lost their study permits as well.

After applying to restore the status of her family, she received another negative response. In the letter that IRCC sent her said that they couldn’t validate her Letter Of Admission (LOA) with her school, a document that confirms that a student was accepted in a Canadian institution. This was despite the fact that she was enrolled at l’École des métiers de l'informatique, du commerce et de l'administration (EMICA) until her study permit expired, and as a result, had to interrupt her studies.

On August 28, 2025, Sanchez and her family applied for permanent residency on Humanitarian and Compassionate grounds.

“There were administrative errors in my immigration file from the beginning. When I say from the beginning, I mean from the moment I made my first visa application,” continues Sanchez. “When I applied from my home country for my first student visa, I received a rejection letter, and half an hour later, I received another letter [from IRCC] saying ‘We apologize, it was a mistake, please send us your passport.”

Currently, Sanchez and her family are sustaining themselves with their savings, which are about to run out. While she waits for a response to her application, she is volunteering at COPSI, helping immigrants and refugees obtain their immigration documents.

“I’m volunteering because it's a personal commitment. I like doing it, I like helping people because I’ve realized that many people face a language barrier when they seek help, and many times hiring an immigration lawyer is expensive and they don’t have the money to pay one,” says Angie.

A lifesaver

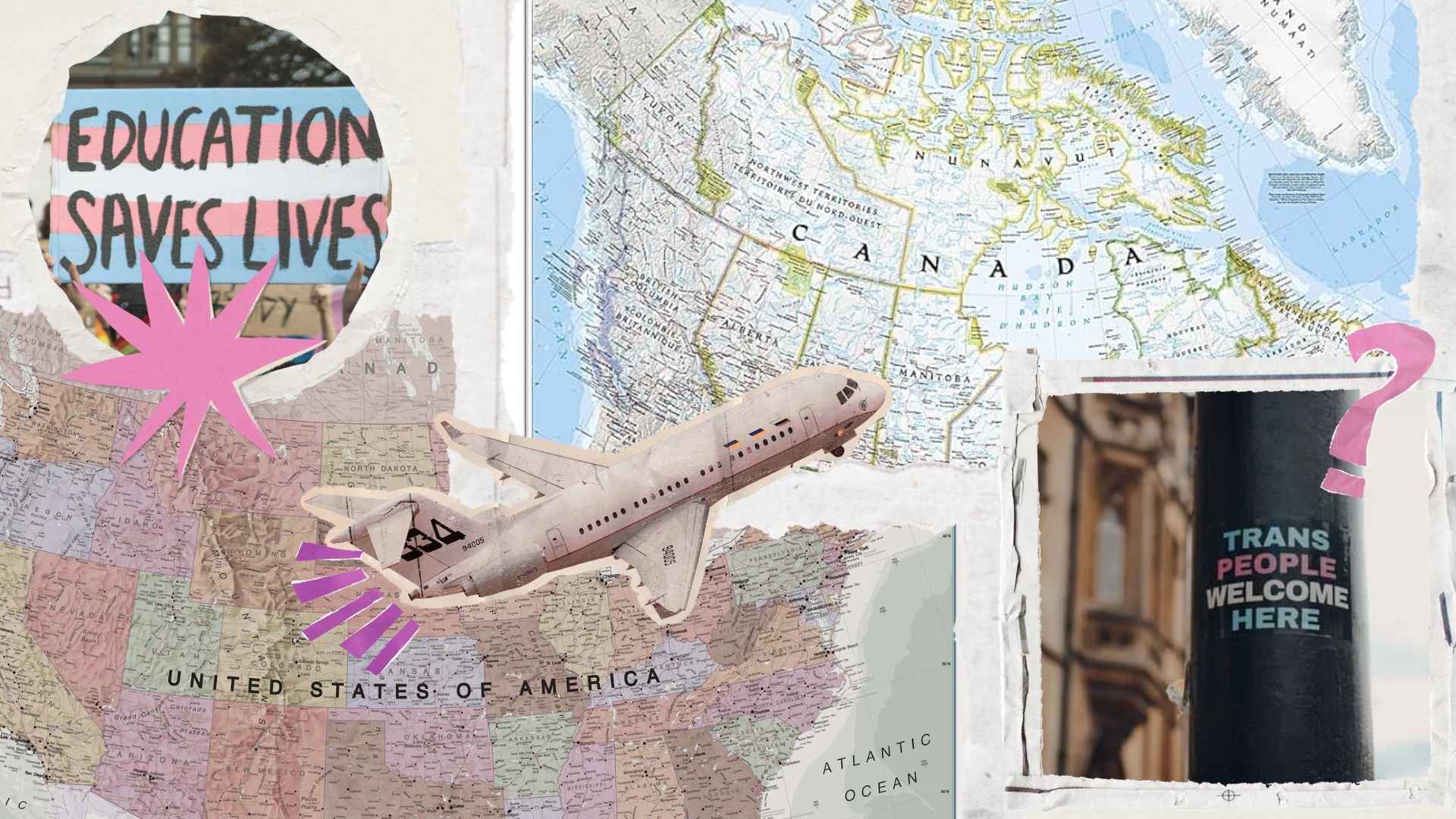

Like Sanchez, many international students, foreign workers and asylum seekers apply for permanent residency for Humanitarian and Compassionate (H&C) reasons. In the case of foreign graduates and workers, many don’t meet the requirements to apply for permanent residency in other immigration programs, such as the Express Entry, that sets a score for each individual depending on their education level, language proficiency, work experience, and skills, among other factors.

More immigrants and refugees seeking to stay in Canada apply for permanent residency on Humanitarian and Compassionate grounds because immigration streams like the Express Entry or the PEQ are highly competitive due to the high demand and the strict eligibility requirements. Immigration applications in almost all permanent and temporary resident categories have also seen higher refusals since 2023.

In their H&C request, applicants must present sufficient reasons that could evoke compassion in the immigration officers who decide whether the applicants deserve to stay in Canada.

“How does one evoke compassion?” asks Deana Okun-Nachoff, managing lawyer of Evolution Immigration Law Group. “It's something quite nebulous.”

The lawyer explains that H&C applications don’t have a checklist of requirements that people must meet, unlike other immigration programs, such as Express Entry. The decisions for Humanitarian and Compassionate reasons are subjective.

As established by previous judicial decisions, the H&C applications that should be approved are the ones with circumstances where “an average Canadian citizen would be moved to try and relieve [the] suffering,” explains Okun-Nachoff, who has more than 20 years of experience working in the immigration field.

However, the rise of asylum claims, and the high competition on other immigration streams are leaving many people without status in the country, something that eventually pushes them to apply on H&C grounds.

“It's like the last lifeline an immigrant has in Canada when there are no more immigration options available,” explains Sanchez.

A race to the bottom

Having success when applying for H&C is now a big challenge for many people.

In 2024, Canada significantly reduced the number of people who can apply on H&C grounds. The Levels Plan aims to “stabilize overall immigration levels and better manage migration programs,” as it is stated by the IRCC.

In 2024, IRCC received 13,750 H&C applications. Angie’s case is one of the 10,000 cases IRCC will receive in 2025. That number is going to continue dropping for the next two years. It will drop to 6,900 next year, and to 4,300 in 2027.

As Okun-Nachoff explains, there is also a limit of applications that immigration officers can approve per year, which increases the probability of receiving a refusal.

“That means the waiting list is hugely long, and now with the low quotas of people being processed every year, there's even a longer waiting time. So we're talking six or seven years from applying to getting a response in principle,” explains Mary Foster, a community organizer of Solidarity Across Borders, a network that advocates for migrants' rights.

The longer waiting time is also due to the immigration office’s current strategy of cutting about a quarter of its workforce in the next three years to reduce spending and return to pre-pandemic staffing. In addition, since each immigration officer is pressured to render a decision in a short amount of time to reduce a backlog, this could lead to haphazard decisions.

Short supply of compassion

Okun-Nachoff, who is also the co-host of Borderlines, a podcast about Canadian immigration law and policy, mentions in one of the episodes that a viable H&C application is the one that would make “the immigration officer cry”.

“It pushes people to create these narratives about their lives, where there is a superhero who is also extremely much of a victim but somehow rises above the victimhood to become this super migrant, [showing] that's why they're good and that’s why white Canada should let them in,” says Foster.

Another ingredient in this perfect storm is that migrants and asylum seekers are currently facing a harder scrutiny and obstacles to secure status. The current immigration system turned the H&C applications into a competition on which case deserves more consideration.

“It's like a race to the bottom. A lot of people who wish to make these sorts of applications don't really jive with the idea of portraying themselves in that kind of victimhood as a way of trying to achieve status because, and it is actually part of the reason that a lot clients of mine don't wish to a refugee claim, they feel the stigmatization,” explains Okun-Nachoff.

Compassion is on the rise due to the multiple conflicts happening in other countries, and the socioeconomic challenges that many people are currently facing, added to the caps on the number of H&C applications accepted, many immigration officers become hardened when reviewing applications, as Okun-Nachoff explains.

“Sympathy now appears to be in short supply. So as demand goes up, there are finite resources, so our sympathy for our fellow humans tends to go down because human beings are self-centered by nature,” explains the lawyer Raj Sharma in the Borderlines episode.

Lack of alternative migration pathways

For Okun-Nachoff, Canada has progressively changed the discourse around migration. In her eyes, what was a welcoming country for refugees and newcomers is now reduced to numbers.

‘’It's looked at in such a weird binary way. It's not with any kind of sophistication, the way that I've felt that it once was. I think we've started doing this weird ‘who's worth more’, which feels Trumpian to me,” says the lawyer.

She says that almost every day, she is contacted by someone who wants to apply for Humanitarian and Compassionate reasons, but doesn’t meet the requirements.

“I am being contacted by doctors, nurses, climate change scientists, like people with advanced post-secondary degrees, many with high degrees of education that they obtained inside of Canada, and those people are not qualifying for permanent residency,” continues Okun-Nachoff. “By contrast, Canada is inviting in large numbers of people who may live outside of the country but speak a minimal level of French, and they are beating out candidates like the ones that I've described.”

In addition to this, her concern is that the majority of permanent residency programs are focused on the economic categories and are leaving aside other migrants, such as people who came through initiatives like the Canada-Ukraine Authorization for Emergency Travel (CUAET).

“Over 150,000 people were invited to do that, and now they don't have pathways to permanent residence. Meanwhile, the conflict is still ongoing in Ukraine, so what are they supposed to do?,” says Okun-Nachoff.

Foster explains that this lack of paths eventually pushes people to live without status in the country after they used their last immigration resort.

“For many people, when they finally get the answer and is a negative answer. What do they do? They have to be there to start again or give up or live out their life undocumented forever,” continues Foster. This is why we are pushing for a regularization program, because there is a huge number of people who are living in need. It’s an absolutely untenable situation”.

A regularization program would mean giving every immigrant and refugee in Canada a status.

“Our demand, from the very beginning, for more than 20 years, has been status for all, and by that we mean everyone should have permanent status now,” continues Foster. “[H&C] is presented as a solution to a problem that shouldn't exist in the first place, especially because it's such a terribly complex and burdensome program that puts all the weight on the person”.

To have a higher chance of succeeding in a H&C claim, Foster says that it’s important to have a lawyer. However, many immigrants can’t afford one. The average fee of an immigration lawyer is around $8000, which creates another barrier for people seeking to have a status in Canada.

“The person who's undocumented by definition has no money to pay a lawyer, does qualify for legal aid, but legal aid pays so little, very few to no lawyers will take the file on legal aid anymore. These [claims] are a heck of a lot of work. You have to gather evidence, then you have to write narratives, and it takes a lot of work to do it well in order to have a chance of succeeding,” explains Foster.

People who can’t afford a lawyer turn to organizations like COPSI where they are referred by workers like Sanchez to professionals who might take their case. “I've lived through all the stages of people coming to see me here seeking help,” says Sanchez. She certainly knows what they’re going through, as she awaits her fate.

.jpg)

%20(1)%20(1).jpg)

%20(3)%20(1).jpg)