Betyna Dorminier is the co-coordinator of the Maison des Jeunes de Pointe-aux-Trembles (MDJ-PAT), in addition to being a youth worker. Since her arrival in the neighborhood in 2017, she has watched “her young ones,” as she likes to say, grow up and take flight into adulthood. They often come back to check on her. We met Betyna at La Caverne, one of the two service points of MDJ-PAT, to understand how the relationships she builds with youth create a bond of trust with them.

On this late July Wednesday, there isn’t a cloud in sight, just a soft blue sky. We join Betyna at the Maison Des Jeunes, located near Richelieu Park, a nostalgic spot for the older residents of the neighborhood: fights, flirting, basketball games, gatherings with friends — everything happened there. It is 1 p.m., an hour before the small house, transformed into a welcoming place, opens. The two co-coordinators, Cendrine and Betyna, are in the living room. One is on her computer, the other is having lunch and waiting for us. On the wall near the entrance, a bulletin board decorated with several photos is hanging: young graduates, selfies from outings, friends laughing — they bear witness to accumulated memories. We head upstairs to the second floor, to an office where it’s cooler.

Betyna grew up in a Haitian family as an only child. Her mother worked long hours to make sure her daughter never lacked food or clothes. “My mother is very generous. When people talk about her, they speak about her the same way they speak about me. They say ‘she will do anything for you.’ I imagine I got that from her,” she says, sitting in a red armchair, legs crossed. In high school, she spent her breaks and summers at her older cousin’s house. “She was my second mother. I can say she’s the person who gave me love in the duo. My mother provides, and she gives me attention and love.”

Born in Montréal-Nord in 1996, Betyna is now a Pointelière at heart. In 2017, when she was 21 years old, a childhood friend and youth worker at La Caverne offered her a job. In the middle of questioning her university studies in mathematics and statistics at Concordia University, she accepted the offer. “University just didn’t resonate with me. Maybe I was biased because of the program I initially chose, I don’t know, but when I asked myself why I was there, I had no answer.” She began her career working part-time for the homework help program “School Perseverance.”

Over the years, the young woman carved out her place within the team. “I came [to the Maison Des Jeunes] because I was looking for a job, and I ended up finding a passion.” Tutor, youth worker, co-coordinator — she has worn many hats during her eight years at MDJ-PAT.

Seeing Herself Through Those She Mentors

Before joining the youth center, at 17, she first worked at a day camp in Hochelaga, where she went by the name Clin d'œil. Immersed in the creativity of the children around her, she joined in their playful imagination. But when she arrived at the youth center eight years ago, she experienced a shock. The atmosphere was different from her previous job. “It was a clash because these are young people who have the same reality as me,” she explains, placing her hand on her chest. “The jokes they tell, I genuinely laugh; it’s not a fake laugh because I’m at a day camp and I have to laugh with you. You say something, I can relate and find it really funny, I can have real conversations with you about things that really happened to me!”

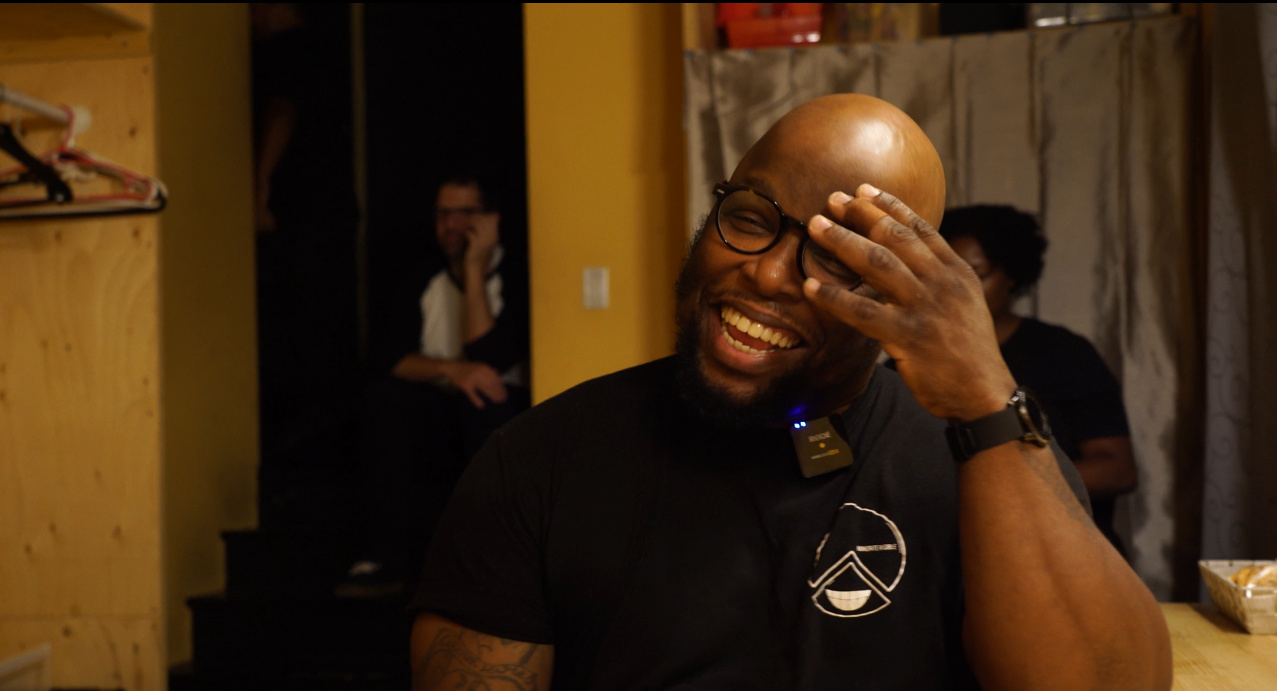

Wearing a black sweatshirt with the MDJ-PAT logo, she says she supervises a summer committee, run by youth to organize summer activities. During the last 30 minutes of their group meetings, she always discusses topics like vulnerability, courage, and leadership. “The first speech I gave was about respect. I asked, ‘How does someone show you respect?’ and I got silence,” she emphasizes, visibly annoyed. “I want to teach them concepts so they can bring them into their lives.” Through this question, the youth understand that respect can be subjective and depends on the relationships between people, Betyna explains.

A question burns on our lips: why does she want to give life lessons to youth?

Behind her clear glasses, her gaze turns to the window. “Generally, my clientele is people like me, second-generation immigrants,” she says, looking back at us. “These are the people with whom I have the best bonds, I understand everything.” According to her observations, the teachings given by immigrant parents are more conservative, far from the reality of Quebec schools. “Sometimes there’s a clash between home and school. Then, the youth just feel misunderstood. Many go to church and I know they’ve received certain teachings. I try to bring these three aspects (home teachings, school, and church), extract relevant points, so that afterward, you make your choices. I don’t want you to think you only have one destiny,” she states, shrugging.

" We created a Safe Space "

The trust Betyna builds allows some youth to consider her a big sister and even a mother, she says. “If you have a panic attack at midnight, call me and I’ll come. It’s already happened to me.” This close relationship also earns her the respect of the youth. “I want the youth to feel heard. My goal is that, in the long term, you tell me what’s going on and I’ll advise you. If I have a good relationship with you, I’ll even tell you what to do,” she says, holding her Tupperware.

If the youth makes choices with which the worker disagrees, she still wants to be informed. This allows her to assert herself, she says, sitting at the edge of the chair. She draws a parallel with the church leaders she attended when she was younger. “At church, I was known for my obedience, but if there was one thing that made me disobey, it was when they asked me to speak in front!” Like the time she didn’t show up to lead the youth service. “Did my leader scold me? Did he hit me? No! He came to me and said, ‘You didn’t come?’ What did he do? Nothing! It’s my choice! It fits with my basic teaching where I advise you, tell you what to do, and then you do what you want.”

Betyna recounts how a bond of trust can be born with adolescents. “There’s a young girl I met at a school who came to MDJ. I said, ‘Hey, hi Sylvie!’ She looked at me and said, ‘You know my name?’” Betyna laughs. If this detail may seem trivial, it confirms to youth that they are not just attendees of MDJ-PAT, but people in their own right. “I remember their names, I try to listen.”

She recalls the time she succeeded in creating trust with a youth suspended from school. Her eyes turn to the window. “He had a background, I think the school suspected him of selling drugs. He didn’t tell me his life. Often, youth don’t share their issues or secrets. I didn’t say to him, ‘What you’re doing is a crime.’ I’m here, I listen.” In this space, he confided that his brother was going to prison. “Sometimes I’d see him in the neighborhood, he’d come here, say hi, but didn’t really talk. When there were too many people, he’d leave. Even if he didn’t come to tell me his whole life, we created a bond!”

Moreover, the shyest youth surprise her, like David*. “Even if he doesn’t talk to me, I tell him I’m happy to see him. I think I’m having a conversation, but I’m more doing an interrogation,” she says with a smirk. One day, he opened up to Betyna. He talked for a long time about a restaurant he had been to, and after several minutes, she wondered why he talked so much. But the next morning, while getting ready for work, she realized it was the first time this youth had opened up so much. “I’m investing in a relationship,” she thought.

These bonds, based on trust, can sometimes break. She leans back against her chair, her voice lowers. “It hurts me… but it’s a risk.” Heavy-hearted, she describes a memorable situation in her journey. “Something happened in the life of my youth, there was an ‘explosion,’ and I was part of it. I took hits… We were at homework help and he crashed out on me in front of everyone,” Betyna continues. “I was shocked.”

However, others show their appreciation for Betyna. It’s common for her and her colleagues to be invited to graduations, sports games, and birthdays. “Their lives aren’t just the Maison Des Jeunes. If you want to impact someone’s life, you can’t stay in just one place.”

Betyna ends the interview and is surprised by how fast time has passed. We head back down to the main floor of La Caverne, where Cendrine is still seated. Tomorrow is a big day: they’re going go-karting at Action 500 with the youth!

*Name changed for privacy.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)