On August 11, 2025, former Maison d’Haïti general director Marjorie Villefranche joins us from the other side of the Atlantic. Freshly retired, she has flown to France, where she will spend the next two months. Behind her screen, she has a smile on her face, and her red glasses are perfectly in place. She shows a certain nostalgia for her years at Maison d’Haïti.

Marjorie Villefranche was its director general from 2011 to April 2025. After 14 years at the helm of the organization, she has just passed the torch to Arcelle Appolon.

Founded in 1973, the organization is a crucial landmark for immigrants and refugees arriving from Haiti. Over the decades, it has evolved into a welcoming body open to all newcomers in the Saint-Michel neighbourhood.

"Maison d’Haïti Saved My Life"

Born in Haiti, Marjorie Villefranche left the country with her brother to flee the Duvalier dictatorship and settled in Quebec in 1964. The exile to Quebec became a necessity, as her childhood already bore the painful marks of her mother's arbitrary arrest, who was imprisoned and beaten by the regime.

Maison d’Haïti is deeply woven into her journey: she first crossed its doors in 1975, became an employee eight years later, and then took over as general director in 2011. Openly juggling her dual Haitian and Quebec identities, she reveals that it was thanks to the organization that she came to understand Haitian culture.

"I didn't know my Haitian culture because I left when I was 12. [...] I first went to Maison d’Haïti, not to work, but to participate in activities and discover my roots," she confides softly.

Paradoxically, it was after she was already settled in Quebec that she immersed herself in Haitian culture: "I think this organization saved my life!" she exclaims. "As a young person, I wasn't at peace with myself. It was only at Maison d’Haïti that I could reconcile with who I was, by understanding this part of me that I couldn't grasp anywhere else."

"Leave No One Behind"

La Converse asked her about the most important professional memory from her time at Maison d’Haïti. It’s a question full of meaning for a woman whose journey has been intertwined with the history of this organisation since 1983. She thinks, then without hesitation, she names the earthquake of January 12, 2010, the moment when everything changed for Haitian communities here and elsewhere.

January 2010.

A powerful, 7,0 to 7,3 magnitude earthquake rattles Haiti. The strongest quake lasts 30 seconds. In the blink of an eye, the capital and its surroundings are reduced to rubble. Several infrastructures are destroyed, and the Port-au-Prince cathedral falls apart.

The human damages of the catastrophe is drastic : 280,000 deaths, 300,000 are injured and 1.3 million are left without shelter.

To this day, this earthquake remains one of the deadliest in modern history.

"We didn't know our capacity to respond to a catastrophe. It was eye-opening for us to succeed in helping hundreds of people who were grieving... to welcome people who were coming from Haiti as well [...] but especially to advocate for the immigration issue at the time of the [Canadian] conservative government, which didn't want to put in place a special program for Haitians, despite the earthquake."

Over the decades, Maison d’Haïti has gone through the difficult and decisive periods of the country it represents. The organization was founded in 1972, at a time of a major migration caused by the authoritarian regime of Jean-Claude Duvalier, known as "Baby Doc," who took office a year earlier, after his father, François Duvalier, known as "Papa Doc."

Prior to the 2010 earthquake, the Maison bore witness to the fall of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986, the AIDS crisis that erupted four years earlier — and the stigma it cast on Haitian people, who were wrongly declared by the Red Cross to be at higher risk of carrying the virus. This was followed by, among other things, the 1991 coup d'état against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Today, the organization is facing a country fractured by gang violence and the recent increase in asylum applications, a consequence of the new Trump migration policies.

Through all these trials, Ms. Villefranche has remained faithful to a principle that she holds deeply dear: "Leave no one behind," she says, referring to the those who have benefitted from Maison d’Haïti's services.

"We Are Here and Nowhere Else!"

The septuagenarian shares that she is torn over passing the torch. While she's taking a well-deserved retirement and has herself supported Apollon in her transition, detaching herself from this organization, which she uplifted and advocated for for more than a decade, still represents a major turning point in her journey. "I was more sad than happy. It was as if something was being taken away from me. On the one hand, I'm happy because I'm leaving with great peace of mind. The person who is replacing me is a good person. But I didn't think I would feel such sadness."

When asked what advice she has to ensure the longevity of the organization now that she has bowed out, she replies: "Don't get bogged down in anecdotes and don't lose sight of our role. We are here to help people and defend their rights. We are here and nowhere else."

Passing the Torch

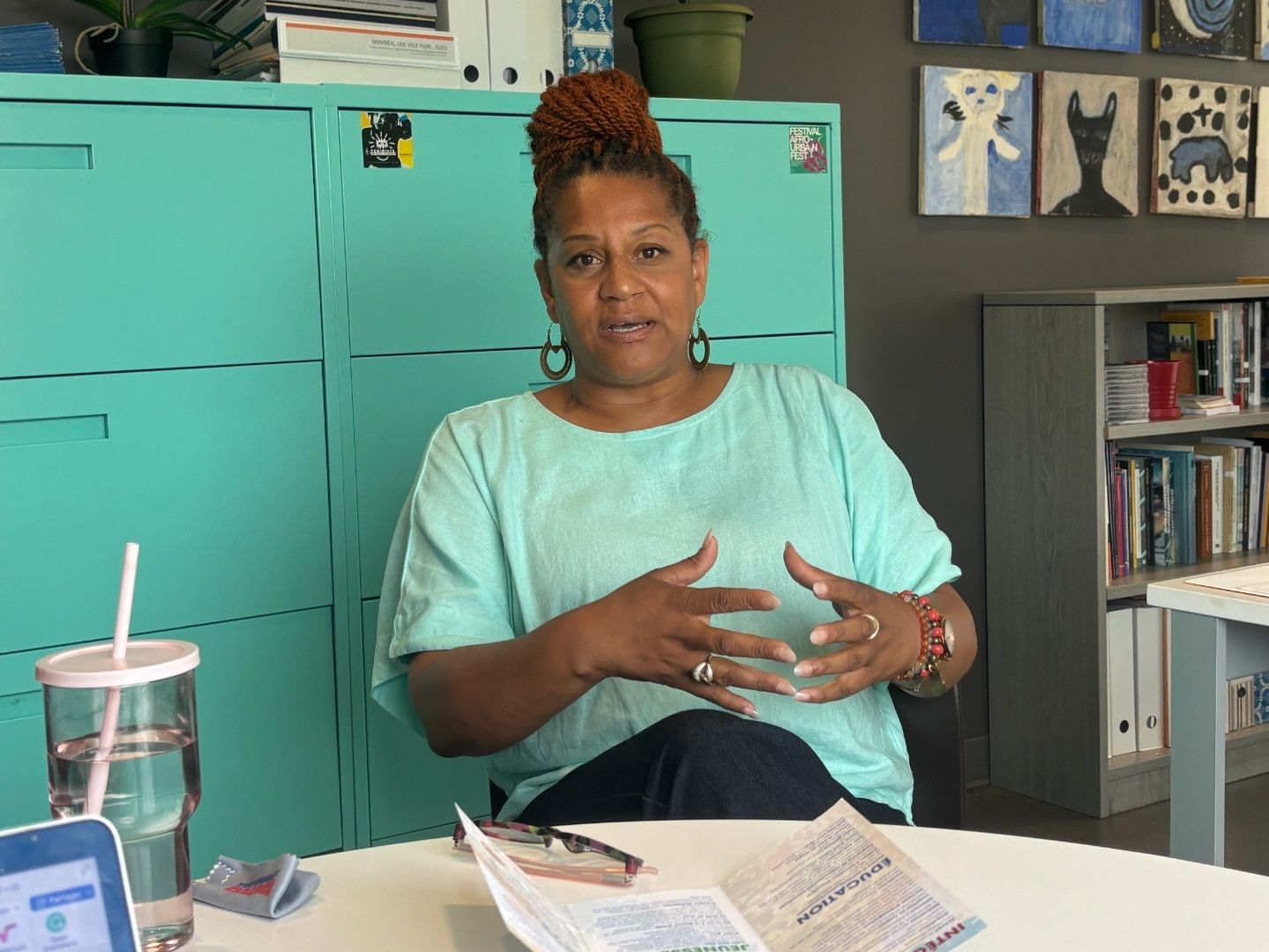

On-site at Maison d’Haïti, Appolon, the new director, is seated with her glasses in her hands. Her turquoise shirt harmonizes with the filing cabinet of the same shade behind her. Her braided hair is pulled up into a bun. With a smiling face, she is ready to answer our questions.

When invited to respond to her predecessor's words, she replies without hesitation: "I find it hard to see how we couldn't take advice from Marjorie Villefranche. As a woman, as a woman from ethnocultural diversity, as a woman involved in her community, any advice from her is welcome."

She agrees with her, insisting that one must not forget "for whom" the organization works. The community organization is there to serve human beings, she insists.

Her voice becomes more lively, and her gaze, more expressive. "When we talk about immigration, we are talking about human beings who, often for involuntary reasons, are forced to make the difficult choice to leave their homes. [...] We make the mistake of thinking that everyone dreams of living in Canada. No, everyone dreams of escaping what is happening in their country."

"Nearly 40 per cent of asylum seekers are children"

Weighing her words, Villefranche continues by saying that one of Maison d’Haïti's most pressing missions right now is to support people in their efforts to bring their loved ones here or to regularize their own status after arriving from the United States. The deadlines are tight, as short as 24 days. Each declaration must be filled out carefully, as it will serve as the basis for the government's evaluation, the former director insists.

Her voice brightens: "You have to understand that when we talk about asylum seekers or immigrants, we seem to forget that it's not just adults. Nearly 40 per cent are children. We must never lose sight of that."

She then talks about cases of family separation at the border, where, for example, only the father, who has family in Canada, can apply for refugee status. The decision is up to the immigration officers: "'You, sir, can enter with the children; the wife, having no ties here, must return to the United States,'" she cites as an example.

She then puts words to a silent but very real tragedy: "Children are left in tears, unable to sleep, wondering why their mother was torn away from them."

Is Quebec a Disappearing Sanctuary?

In April 2025, Quebec Premier François Legault stated that the province had reached its maximum capacity to welcome new immigrants due to the significant number of asylum seekers, primarily of Haitian origin.

Villefranche and Appolon react to these comments. The former doesn't mince her words. "It's an extremely hypocritical position, because today, the chamber of commerce says we need 100,000 immigrants per year," she blurts out.

The retiree is referring here to the comments of the Federation of Quebec Chambers of Commerce (FCCQ), which stated on August 11 that the province will have to welcome more than 100,000 immigrants per year by 2029 to meet the current needs of the labour market. This observation is based on data from the ministry of employment.

"These families are not [immigrating] for fun. They are looking for a way out and not to die. To reply that the yard is full... full of what? Bad will, to put it simply," the former director adds. Villefranche immediately recalls the special program put in place for Ukrainians, under which 100,000 visas were issued to them. "Why wouldn't we have a special program for Haitians?" she asks. As for the province's capacity to welcome asylum seekers, she reminds us that they must have family here to apply. For her, the increase in asylum applications concerns the families more than the province.

As the new director of Maison d’Haïti, Appolon is more cautious in her response. "As a Quebecer, I am very proud to see what we have done to welcome Ukrainians here in Quebec. It should be known that the current situation in Haiti is no less serious for the population," she says, seeming to refrain from saying more.

Looking to the Future

On the idea of succeeding an emblematic figure of the community sector, Appolon adds that she approaches everything "with humility." For the future, she tells us to ask ourselves the question: "What do I have in my djakout that I can bring [...] to honour the vision of those who came before me?"

Her main battle is funding. She admits having to cut three programs previously offered by Maison d’Haïti for now, due to lack of resources. One of them is Le Projet Gars (The Boys Project), which had a mission to raise awareness about toxic masculinity and was dedicated to boys from Haitian communities.

In the current context, Maison d’Haïti is experiencing high traffic, as we saw during our visit, when about thirty people, including asylum seekers, were on site to ask for support.

Her Final Word

Villefranche wants to remind us that Canada has benefited enormously from the contribution of the Haitian community. The founders of Maison d’Haïti, Adeline and Max Chancy, were part of the first influx of Haitian migrants to Quebec, known as the "brain drain." This movement, which occurred in 1965 and describes the fleeing of the dictatorship of Duvalier Sr., was named as such because the migrants who were part of it were highly educated. The Chancy's contribution to Quebec society illustrates the contribution that Villefranche refers to. From Chancy to Appolon, the latter sees the legacy of the former general director as "a strong legacy, a rich legacy, a legacy that we collectively have the responsibility to carry forward," referring to Villefranche's many decades of community involvement and activism.

As the interview comes to an end, Villefranche asks us if we had noticed the number of artworks arranged in the building during our visit to Maison d’Haïti. "That's what the Haitian community looks like," she continues. She talks about the "beautiful" exterior of Maison d’Haïti, and its interior which is just as colourful.

This art, colorful and alive, symbolizes for her what Haiti has to offer and continues to give to Quebec.

*Djakout : "bag" in creole.

Did you enjoy this article?

Every week, we send out stories like this one—straight to your inbox.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)