The arrest of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces, following a military operation carried out in Caracas during the night of January 2–3, triggered a global diplomatic shockwave. In Montreal, the intervention has also revived very specific memories. For immigrants from Latin America or the Middle East who settled in Quebec after experiencing wars, coups, or foreign occupations, the U.S. offensive in Venezuela fits into a long history of interference. From the Monroe Doctrine to its revival under Donald Trump, this is a look back at two centuries of American interventionism—and at how these geopolitical decisions continue to resonate in the migration journeys of people who have made their lives here.

Thousands of kilometers from Caracas, the U.S. intervention in Venezuela has rekindled lived experiences for many immigrants in Montreal—people from countries marked by decades of foreign interference. For them, the operation carried out by Washington is not merely international news, but part of an intimate and collective memory.

For Carolina Echeverria, a Chilean living in Quebec, January 3, 2026 recalls a childhood and youth spent under the dictatorship that followed the 1973 coup d’état.

“I was nine years old at the time of the coup. My entire adolescence, my youth, my student life—it all took place during Pinochet’s dictatorship,” she says, describing a period marked by fear, restrictions, and political violence. “I didn’t have a normal youth. Going out at night with friends, expressing yourself freely—everything was harder. These are things you never forget. Cruelty and fear stay with you for life.”

From a right-wing family, Echeverria left the country at 21, as soon as she reached the legal age of majority at the time. Still, she describes a form of inner exile. “At university, I feared for my life. I was incapable of formulating my own thoughts. When family or regime thinking imposes itself, it creates another kind of fracture, another exile.”

Faced with the U.S. operation in Venezuela, she refuses any direct comparison with Chile in the 1970s. “Chile was a democracy before the coup. We had freely chosen our president (Salvador Allende). Venezuela is experiencing a deep crisis, with millions of people having left the country. It’s not comparable.” She does, however, see a common thread: “The United States has always allowed itself to manage other countries’ affairs. They did it in Iran, Chile, Argentina, Peru, Bolivia. They planted dictatorships throughout Latin America.”

Ms. Echeverria, a member of the Crear Poder Popular collective, believes these interventions have durably hindered the continent’s development. “They set our countries back 50 years. It took decades to rebuild what was destroyed.” Today, she says she sees a world where “law and rights no longer exist. The strongest does whatever they want.”

Lasting Traumas

This sentiment echoes the path of Salam El Mousawi, an Iraqi who arrived in Canada in 1990, one month before the outbreak of the first Gulf War. From Montreal, he followed the bombings of his country—first during the Gulf War, then again in 2003, during the cycle of interventions launched by the U.S. military after 9/11.

.jpeg)

In his view, the main objective of the intervention was clear: “Control of oil. Iraq has some of the largest oil reserves in the world. Weapons of mass destruction and security were pretexts—they were fallacious.” He also draws a parallel with Venezuela, which he describes as “strategic” for Washington.

The two U.S. wars in Iraq also allowed the United States to establish a lasting military presence in the region. “They set up bases in Kuwait to carry out ongoing attacks, in Saudi Arabia and in other countries, particularly between Bahrain and Qatar,” El Mousawi explains.

The consequences of these interventions, he continues, were immense. “The victims number in the tens, hundreds of thousands! And wars produced other wars—Al-Qaeda, then ISIS. The Americans were present, but they let it happen to pressure the Iraqi people.” He recalls that the United States had previously supported Saddam Hussein, notably by providing weapons and intelligence, before overthrowing him.

While Salam El Mousawi acknowledges that Iraq later began a gradual reconstruction, he insists on the enduring nature of the trauma. “They’re still there. The largest U.S. embassy in the world is in Baghdad. Their presence is constant.” In his view, American interventions inflicted disproportionate violence on peoples unable to defend themselves on equal footing.

Both immigrants living in Montreal also highlight the persistent misunderstanding, in Canada, of the realities experienced in their countries of origin. “People confuse information with truth,” says Carolina Echeverria. Salam El Mousawi points to media coverage that often reduces these countries to “problem zones,” retrospectively legitimizing interventions. In Montreal, their stories serve as a reminder that behind doctrines and military operations, entire societies continue to bear the scars of decisions made elsewhere.

Venezuelan Perspectives: Between Relief and Mistrust

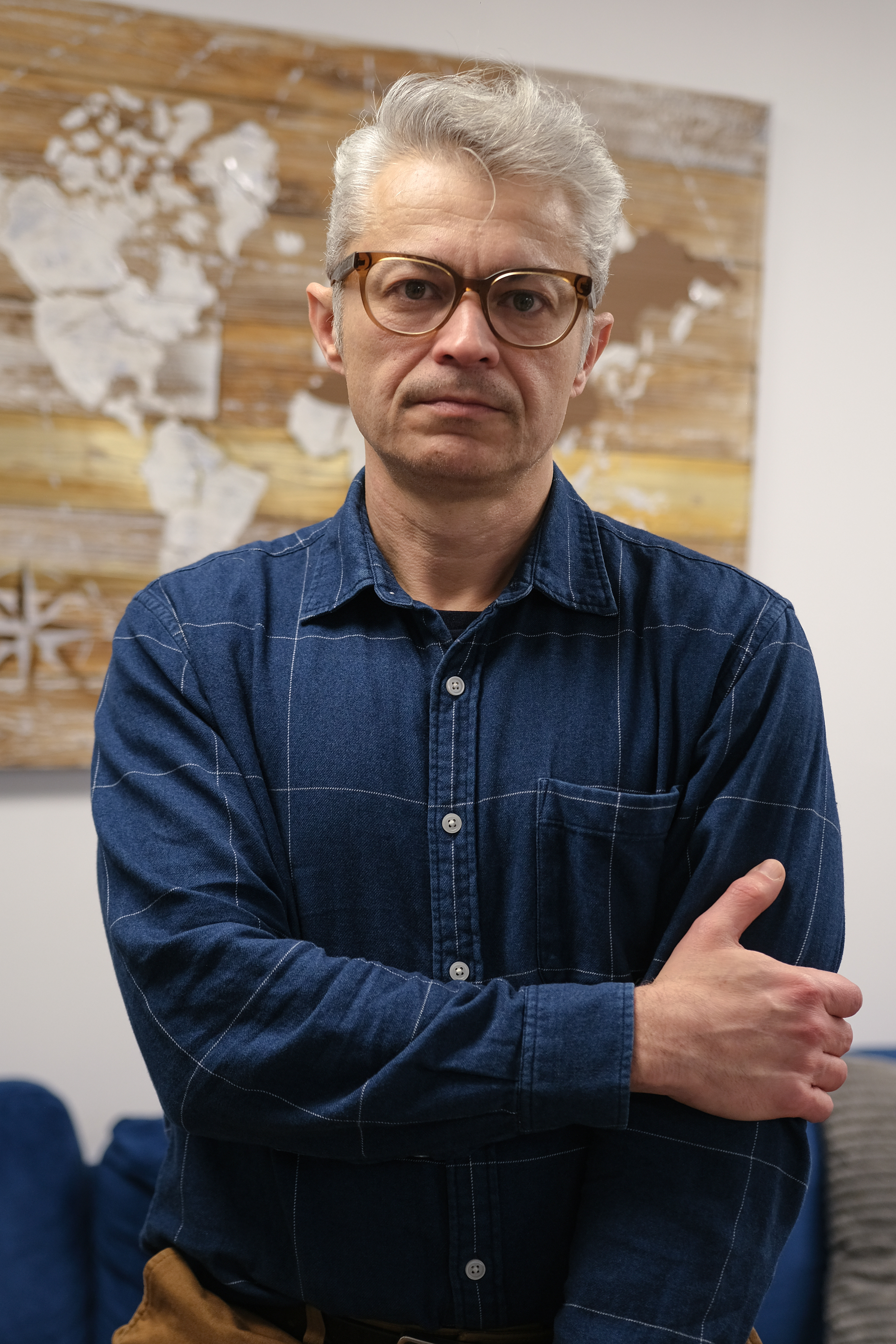

A Venezuelan journalist living in Canada since 2014, Rafael Osio Cabrices is editor-in-chief of Caracas Chronicles. A long-time opponent of the Chavista regime, he says he learned “immediately” about the U.S. military incursion into Venezuela and the arrest of Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores.

While he acknowledges that the January 3 operation took place in a context of mounting pressure from Washington (sanctions, indictments, military presence in the Caribbean), Osio Cabrices points out the gap between U.S. justifications and the expectations of the Venezuelan population.

“From the American point of view, Maduro leads a drug-trafficking operation. For us Venezuelans, the main reasons he should be in prison are torture, kidnapping, and the murder of thousands of people—peaceful protesters.”

Even among regime supporters, he says, Maduro’s responsibility for the country’s collapse is widely recognized. “Maduro and his collaborators are responsible for the deterioration of living conditions and the humanitarian and economic collapse that forced a quarter of the Venezuelan population to emigrate in less than ten years.” He himself can no longer return to Venezuela: his passport has been annulled, he says, and many of his colleagues have been attacked or forced into exile.

Despite the professional distance he maintains as a journalist, the questions he answers consistently bring up a wave of emotion, quickly visible on his face. Asked whether Venezuelans can trust Donald Trump’s U.S. government to meet their aspirations and allow them to flourish in democracy and freedom, he pauses before responding. “I have a hard time believing that a leader like Donald Trump, who threatens democracy in his own country, truly cares about promoting democracy elsewhere,” he says.

He nonetheless observes that since January 3, the Chavista regime has begun to crumble. “At the time we’re recording this video, political prisoners are finally being released,” Cabrices reports—an outcome he previously would have deemed unthinkable.

From Monroe to “Don-roe”

Articulated in 1823 by President James Monroe, the Monroe Doctrine aimed to prevent European interference in the Americas in exchange for a U.S. commitment not to intervene in Europe. Initially conceived as a defensive strategy, it gradually became a central tool of U.S. influence in Latin America.

In the early 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt expanded the doctrine’s scope, authorizing Washington to intervene in countries deemed unstable in order to preserve order and American interests. This interpretation laid the groundwork for numerous military and political interventions in the region.

A century later, Donald Trump followed in this tradition by invoking the Monroe Doctrine to justify the arrest of Nicolás Maduro, even referring to a “Don-roe Doctrine.” For many political scientists, this shift is not a rupture but a reaffirmation: the doctrine no longer seeks to contain external powers, but to legitimize direct domination in the name of security, energy, and U.S. strategic interests.

A Panorama of U.S. Interventions

The operation in Venezuela fits into a long history of American power projection. After World War II, the United States emerged as a global economic and military power and multiplied operations to defend what it defined as its strategic interests.

Major direct interventions include the Vietnam War (1960–1975), the 1989 invasion of Panama and the ousting of Manuel Noriega, and the wars in Iraq in 1990 and 2003. Following the September 11, 2001 attacks, Washington launched military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, and elsewhere. According to Brown University’s Cost of War Project, these post-9/11 interventions resulted in approximately 4.5 million direct and indirect deaths.

At the same time, the United States carried out numerous indirect interventions. The CIA participated in the overthrow of governments in Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), and Chile (1973), and supported local armed forces in Central America during the 1980s. These interferences have durably shaped the political and social trajectories of many regions.

January 3, 2026: The Shockwave

On January 3, 2026, U.S. armed forces launched a military operation in Caracas, bombing several strategic sites before capturing and extracting President Nicolás Maduro and his wife. Washington justified this intervention against a sovereign state by citing the fight against “narco-terrorism,” accusations examined during a trial held in New York on January 5.

The operation prompted a wave of international condemnation during an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council. Secretary-General António Guterres reminded members that the use of force violates the UN Charter. Russia and China demanded Maduro’s release, and several Latin American countries expressed concern over a resurgence of interference in the region. In closing remarks, Denmark stressed the inviolability of borders, while Donald Trump repeated his threats to annex Greenland.

American expansionist ambitions are also resonating in Canada, where President Trump’s renewed remarks about making the country the “51st state” of the United States are fueling concerns about Washington’s intentions and the place of international law among allies—fears intensified by the intervention in Venezuela.

Between Hope and Caution

This operation marks a pivotal moment in a policy with deep roots, one that now sends chills through many nations witnessing the United States’ drift away from international law. Still, for Rafael Osio Cabrices, it is also a moment of hope for his people, as he emphasizes the priorities expressed by a large segment of the Venezuelan population. “For us, exile is a trauma. Being able to return and see our families again is more urgent than democracy.”

Despite the uncertainty, he sees a possibility. “Venezuelans now have reasons to hope,” he says—provided the transition unfolds without vengeance. “Justice is not revenge, and violence cannot be the solution.”

.png)

.jpg)